Diagnosis and how your GP can help

Diagnosis and what to expect How your GP can help Conditions that can be confused with vitiligo How vitiligo is diagnosed Can I self diagnose vitiligo?

Vitiligo Diagnosis: What should I expect?

The best way to know if you have vitiligo is to go and see your doctor. You can even prepare for your visit by doing the following:

- Reviewing your family medical history.

- Making notes concerning any stressful events that have occurred in your life.

- Making a list of chemicals you may have come into contact with.

- Considering taking a friend or family member with you for support.

- Preparing a list of questions to ask your doctor.

During your visit, your doctor will ask several questions concerning various areas of your life including family history and whether you have had any injuries. If available, your patches will be examined using a ‘Woods Lamp’ (ultraviolet lamp) which will assist in narrowing down and eliminating the possibility of it being another skin condition.

You can also prepare for your appointment by familiarising yourself on how your GP can help and by downloading and reading our Vitiligo E-book, The Definitive Guide to Vitiligo.

How your GP can help

GPs have access to a wide range of resources to help you manage your vitiligo – but with most appointments only lasting about 10 minutes, it’s really important that you are aware of the ways in which your doctor can help. During your appointment you can request different kinds of support from your GP, and we hope this will give you an insight into what you can ask for, and help you prioritise your time during your appointment.

Here are the 7 ways in which your GP can help you, at any stage in your vitiligo journey:

Providing information about vitiligo

GPs can provide you with lots of useful information, the key important things we advise you ask about include:

The Knoeber Phenomenon and how it may affect your daily life and routines. Avoiding trigger factors such as friction and trauma may help to reduce new depigmentation, so it’s important to understand how your environment may be affecting your vitiligo.

A number of treatments are available, and we are beginning to see more and more treatments undergo clinical trials – so as these (hopefully) become available, it’s important for you to understand what is available to you. Your doctor is the best source of information for this, or our Society can help advise you on what’s available for you to research ahead of your appointment..

They should tell you about charities that can help you. The Vitiligo Society provides support and education for people with vitiligo and their families/carers, and raises awareness about the condition. It has an online community and local support groups. The patient information About vitiligo may be helpful.. The UK charity Changing Faces (website available at www.changingfaces.org.uk) provides details of local skin camouflage services, a telephone helpline, and online support forum; both are recommended for referral by the NHS to its practitioners.

Advising on the importance of effective sun protection and vitamin D supplementation

Most of us know that sun protection is very important. Some NHS Trusts may still provide sunscreen on prescription, but not all. High-factor sunscreen with protection against ultraviolet A and B (for example Uvistat® or Sunsense®) can be prescribed (these are classified as ‘borderline substances’ and the prescription must be endorsed ‘ACBS’). Your GP can advise on this and also provide advice on the need for 4-star or 5-star UVA rating and sun protection factor 50 to people with vitiligo. They can help you understand the importance of application to affected patches and surrounding skin before going outdoors into the sun.

In addition you may consider asking your GP about your vitamin D requirement. The body creates vitamin D from direct sunlight on the skin when outdoors, so when people living with vitiligo avoid the sun or use High SPSF sun protection, this can lead to a deficiency in vitamin D. Your doctor can advise on supplements and diet to help address this.

Offer a referral to a skin camouflage service

Skin Camouflage can be a powerful tool in helping you live happily with your vitiligo. Highly pigmented cover creams and powders are available in a range of shades and colours that can be colour matched to the person’s skin tone. They are lightweight, waterproof, and easy to apply to the face and anywhere on the body after training. They may remain on the face for 12–18 hours, and on the body for up to 4 days.

A local skin camouflage service may be available through your local dermatology service – your GP can advise on this and make this referral for you. They may also suggest that you self-refer to the charity Changing Faces, which provides education from skin camouflage practitioners on the use and application of cosmetic camouflage creams and powders. The website (available at www.changingfaces.org.uk) provides patient information on Skin camouflage, details of local skin camouflage services, a telephone helpline, and online support forum.

Your GP can also talk to you about alternative options to camouflage such as self-tanning products that provide lasting colour for up to several days. Cosmetic micropigmentation and tattooing which is a more permanent option.

Offer support for any psychological symptoms or conditions that have resulted from your vitiligo

Vitiligo is more than a cosmetic condition, and it can seriously affect your self esteem and confidence. This in term can have a dramatic affect on your mental wellbeing. Your doctor should be asking questions about the impact of vitiligo on your daily life, and whether it’s making you feel anxious or depressed in any way. Never feel you have to down-play how vitiligo is affecting you psychologically and socially., and if you need support for this then make it clear to your GP. They have the ability to refer you for emotional and psychological support – don’t be afraid to push to get access to this help at any point in your vitiligo journey.

Offer treatment options

Currently the first treatment you may be offered is a potent topical corticosteroid once daily for up to 2 months. You will likely be prescribed this if you meet all of the following criteria: An adult with non-segmental vitiligo that is localized or limited (affecting less than 10% of the body surface area); Treatment is not applied to the face; For women, they are not pregnant; There are no contraindications to corticosteroid treatment. If you are given this you should also be scheduled for a review after one and two months to monitor your body’s response to it.

Arrange referral to a dermatologist

If you do not meet the above criteria or you do and have not had success with the prescribed treatment then your GP can arrange a referral to a dermatologist where other treatment options may be discussed. We hear that a lot of people get referred but never hear from a dermatologist – don’t give up! If you need this help then keep following it up until you get the help you need. You GP may also be able to help you explore other treatment options whilst you wait for your referral – they can do this by seeking specialist advice on treatment options.

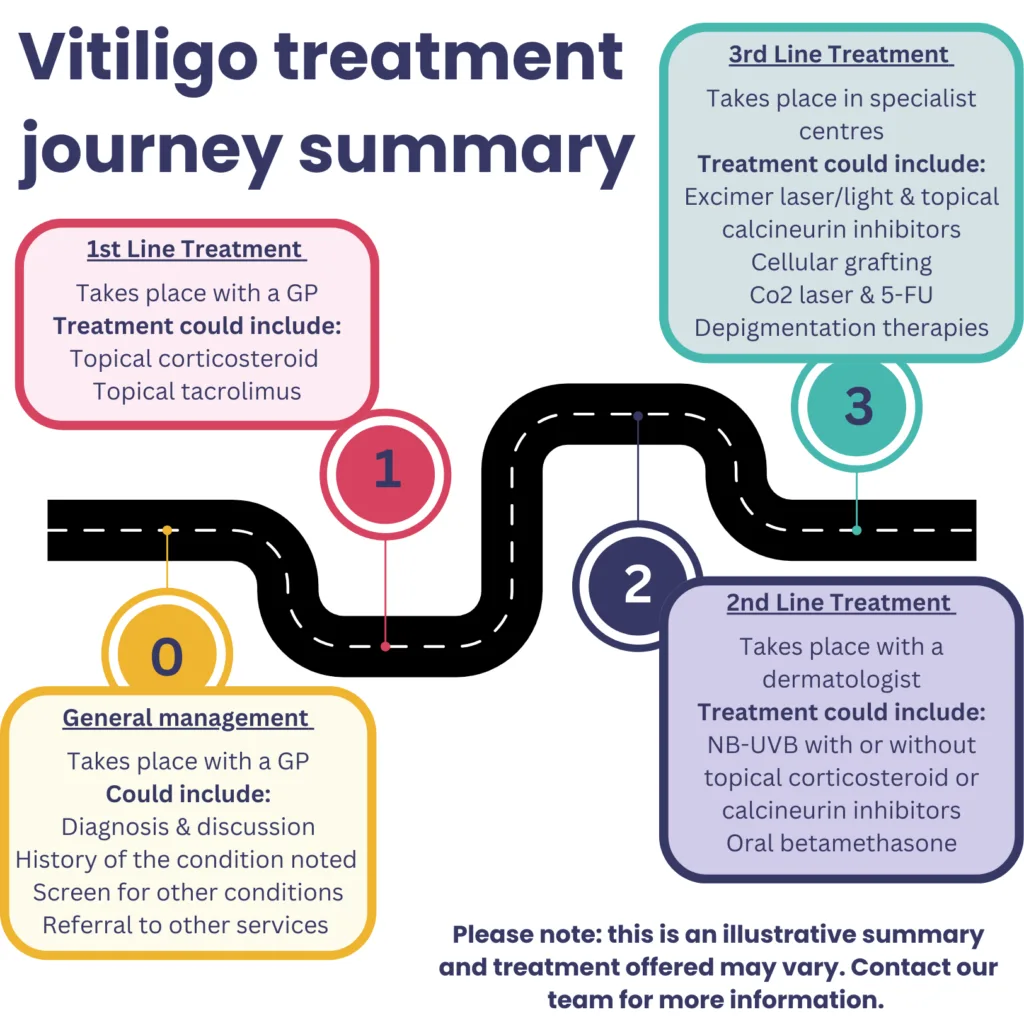

A dermatologist appointment is important as a dermatologist can support you in accessing specialist treatments that are referred ‘second line’ treatments, that your GP may not be able to offer. Below is an illustrative summary of the vitiligo treatment pathway in the UK:

Check for, and arrange an investigation on any potential coexisting autoimmune conditions

There are a number of conditions that seem to be common in people with vitiligo. Vitiligo might share certain genetic or environmental risk factors with other conditions. Certain immune cells and processes that trigger inflammation in vitiligo also play a role in some other conditions. Your GP can check for these conditions and arrange a further investigation if they suspect you may have one.

if you have any questions before or after your GP appointment then please don’t hesitate to get in touch with us, we’re here to help: hello@vitiligosociety.org.uk

Conditions that can be confused with vitiligo

There are a number of conditions that can be confused with vitiligo, some common and some relatively uncommon – all of which may present with areas of depigmentation that can mimic vitiligo.

Conditions present from birth (Congenital)

- Albinism — a generalized loss of pigment that includes the eyes and is evident from birth, with ocular abnormalities such as strabismus and nystagmus. It is caused by defective manufacture of melanin.

- Piebaldism — an autosomal dominant condition in which there is an absence of melanocytes in affected areas of the skin. It usually presents at birth with a white forelock of hair, anterior body midline depigmentation, and bilateral shin depigmentation. The patches remain unchanged throughout life.

- Tuberous sclerosis — an inherited disease, characterized by ash-leaf shaped, depigmented macules on the trunk. It usually presents in early childhood, and other skin features include facial angiofibromas or periungual fibromas.

- Incontentia pigmenti achromians of Ito (hypomelanosis of Ito) — characterized by depigmented whorls on the legs or trunk, usually in babies or small children. There may be associated disorders of the musculoskeletal system, eyes, teeth, and central nervous system.

- Naevus anaemicus — a congenital disorder causing hypopigmented patches due to localized vasoconstriction.

- Naevus depigmentosus — segmental hypopigmentation that is usually present at birth or in the first year of life, lesions may increase in size in proportion to the growth of the child.

Conditions that occur after skin inflammation or injury (Post-inflammatory)

- Chemical/occupational depigmentation — for example caused by phenolic/catecholic derivatives that are cytotoxic to melanocytes. Sources include adhesives, de-emulsifiers used in oil fields, deodorants, disinfectants, duplicating paper, formaldehyde resins, germicidal detergents, hair dyes, insecticides, latex gloves, motor oil additives, paints, photographic chemicals, plasticizers, printing ink, rubber antioxidants, soap antioxidants, synthetic oils, varnish, and lacquer resins.

- Hypopigmentation following any inflammatory skin condition, including eczema, psoriasis, lichen planus, scleroderma or systemic sclerosis, lupus erythematosus, and syphilis. It can be distinguished from vitiligo by being hypopigmented rather than depigmented.

- Morphoea — a localized thickening of the dermis due to excess collagen. It is most common in women aged 20–40 years.

- Lichen sclerosis — characterized by itchy, white atrophic plaques in the perineum, which may mimic mucosal vitiligo.

- Pityriasis alba — variously defined as either a form of eczema or a form of post-inflammatory hypopigmentation following mild eczema. It is relatively common in children with darker skin, in whom multiple, poorly defined, hypopigmented, non-scaly, round to oval patches with ill-defined borders are seen on the face, neck, and trunk. In people with paler skin, it may only be visible in the summer when the normal skin tans.

- Post-traumatic leukoderma — may occur after deep burns or scars.

Infective conditions

- Progressive macular hypomelanosis — a common disorder in people of African or Afro-Caribbean origin characterized by ill-defined macules on the trunk, often confluent in and around the midline, and rarely extending to the proximal extremities, head, or neck.

- Pityriasis versicolor (or tinea versicolor) — a superficial yeast infection that can cause loss of pigment, particularly in young adults with darker skin. It presents as small (less than 1 cm in diameter), round, pale hypopigmented or pink macules, which have a fine, dry surface scale. They are usually found on the neck, upper trunk and chest, abdomen, and proximal extremities. See the CKS topic on Pityriasis versicolor for more information.

- Tuberculoid leprosy — can cause hypopigmented patches (usually one to five patches) with a raised red-copper coloured border. The patches can be distinguished from vitiligo in having reduced sensation to touch, and there are usually other features such as enlarged cutaneous nerves.

Conditions involving tumor growth (Newplastic)

- Melanoma-associated depigmentation — occasionally, a halo of depigmentation is seen around a malignant melanoma. It differs from that seen in a benign halo naevus by being irregular and asymmetrical.

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides) — usually seen on the trunk and proximal extremities, especially the buttocks and pelvic girdle, and can present as scaly or non-scaly dry, hypopigmented round patches, with the skin having a typically ‘wrinkled’ appearance.

Other conditions

- Drug-induced depigmentation — for example due to corticosteroids, chloroquine, fluphenazine, physostigmine, and imiquimod.

- Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis — a common condition characterized by multiple, discrete, circumscribed, porcelain-white macules distributed symmetrically on the trunk, arms, and legs. Lesions tend to favour sun-exposed sites.

- Halo naevus — a mole with a regular, symmetrical halo of depigmentation around it. It is caused by an immunological reaction against melanocytes and, eventually, the mole disappears. They are benign, common in children, and occur more often (compared with the general population) in people who also have vitiligo.

- Sarcoidosis — hypopigmented macules may occur over granulomas in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue.

How vitiligo is diagnosed

There are a number of characteristics that healthcare professionals may look out for when diagnosing vitiligo:

- Depigmentation of areas of skin (or hair)

- Characteristic of depigmentation areas including: colour, margins, extent and distributions, location, exhibition of the Koebner Phenomenon and progression.

Your GP may ask you a number of questions such as:

- The number of patches you have and how the patches have progressed

- The impact on your quality of life

- If you are aware of any triggers that may have caused the onset or be making your vitiligo worse

- If you have any family history of vitiligo

They may also carry out an examination taking into account:

- The distribution of your patches

- Presence of the Keobner Phenomenon

- The % of body surface affected

- They may test for associated conditions or your vitamin D level

Can I self diagnose vitiligo?

We would always suggest seeking a formal diagnosis of vitiligo from a trained healthcare professional. However, there are some signs and symptoms that you can look out for if considering if you might have vitiligo.

Vitiligo manifests in loss of pigmentation in the skin and/or hair. The patches of depigmentation are usually asymptomatic, but many people report that their patches can be itchy.

The patches may at first appear hypopigmented (low in pigment) and pale before eventually turning white in colour. sometimes the patches may be white in the middle surrounded by a pale area of skin. Patches are usually clear in shape, and their boarders may be smooth or irregular.

Patches can appear anywhere but are more common around the eyes, nostrils, belly button, an genital areas. Sometimes vitiligo can be symmetrical and other times not. Sometimes vitiligo can appear as a result of damage to the skin, known as the Koebner Phenomenon. Hair roots can also be affected, resulting in white eyelashes, brows and hair.

If left untreated patches will usually enlarge and spread over time, although it’s rare that they will cover almost all your skin. It is possible for vitiligo can stabilize over time, without treatment.

Read more

Research & Treatment

Visit our Member Magazine

Povorcitinib – what you need to know about this potential new treatment

Research & Treatment

Visit our Member Magazine

Ritlecitinib – a new vitiligo treatment?

Research & Treatment

Visit our Member Magazine

Everything you need to know about the use of phototherapy for treating vitiligo

Lifestyle

Visit our Member Magazine

Our community nominate their top 3 cosmetic camouflage products for vitiligo skin